Lessons in Architecture: Rhythm and Pattern

Seeking form and function

Tidal currents, continuously hitting the shoreline and receding through the day, often leave behind their traces in regular patterns known as sand waves. These are simple and charming compositions of life and geometry that are formed organically. While they appear as lines and depressions, there is broadly a rectilinear pattern with continuous movement within the lines, giving an impression of movement and activity. Such delightful patterns and rhythms are also experienced in good architecture, outside the rigidity of form, structure and repetition. Even simple houses in a village community, or stores and shops on a commercial street display variations on a common theme that break monotony, while creating cohesive architecture. The simplest technique for an artist or architect to express rhythm is the absolute repetition of the same elements, such as windows or openings, a pattern of solid-void-solid-void, just like simple music beats of one-two-one-two. This may be too simplistic and dull for the eye, and is too perfect to be found anywhere in nature, unless designed by intention. Therefore, an architect seeks a pattern more complex, but also appealing.

Goa, a coastal state in the south-western part of India, was occupied by Portuguese settlers for over four centuries. Fontainhas, a residential area, also known as the Latin Quarter, is probably the most visible architectural legacy that is well preserved. It is a variegated maze of narrow streets away from the hubbub of the waterfront. The architectural quality is essentially similar - residential homes, two storeys high with repeating patterns of windows and doors for each house that create a kind of symmetry, broken only by bright colours and embellishments. The windows are rectilinear, one above another and formed in broad and heavy moldings, expressively characteristic of colonial ideals. They are illustrated in shades of green, pale yellow and blue, along with with red-colored tiled roofs, artistic doors, oyster shell, window panes, intricately designed iron railings and overhead balconies and extended front porches, with narrow passage and landscape around. This imparts a unique sense of rhythm to the streets that distinguish the neighbourhood from the rest of the city. While this style of architecture is of a bygone era, it has been adapted over the years with some houses being used as cafes, stores and art galleries.

On the other hand, in the French Quarters of Pondicherry, a coastal city in the south-eastern part of India, there exists a different rhythm. It arose from the French preference for two windows separated by a large expanse of wall, which thrusts the windows nearly to the corners. So from the outside, it is not clear which windows belong to which house, building or room, because they are similarly, but also dissimilarly spaced. This rhythm is slightly more complicated, although very simple to perceive.

Architectural rhythm is experienced very differently from say, musical rhythm. Musical rhythm grips the listener after a certain point. Often, the body responds physically by way of foot tapping or clicking or some such movement. Architectural rhythm takes time to mentally assimilate and is experienced differently by different people. It is hard to define the experience since architecture itself has no dimensions of movement and time, unlike the performance arts. Often, it is the architect, at the drawing table, who experiences the rhythm in the creative process on paper. This experience is usually far removed from that of the viewer, ultimately.

Like ancient Hindu architecture, traditional Indian classical dance is also an art form that portrays the spiritual through the physical. Both art forms are based on the concept of movement originating at a single point, and relating to a vertical axis. Whereas in dance, this point of origin is the navel conceived as the mid-point of a circular mandala (a geometric configuration of symbols used as a spiritual tool for establishing sacred space), positioned frontally and vertically, divided into four quarters by vertical and horizontal axes passing through the navel; in Hindu temple architecture, the mandala is both horizontal, aligned with the four cardinal directions, and three-dimensional, with a central, vertical axis rising to the point at the summit. Subsequently, both the art forms have influenced each other by way of patterns in architecture and rhythm in dance.

The movements in the Bharatnatyam style of dance, are conceived in space mostly along straight lines or triangles. The linear pattern of the temples of Tamil Nadu has influenced its geometric patterns. Odissi dance style has a vast range of sculptural body movements which give the illusion of such sculptures coming to life. The circular temple architecture of the Jagannatha Temple, Puri has influenced the geometric movements of Odissi. So in temple architecture, we see a petrification of the dancing rhythm, both belonging to a classical period. This also follows the simple principle that, if the objective of architecture is to create a framework around human lives, then its form must follow the function that it would encapsulate.

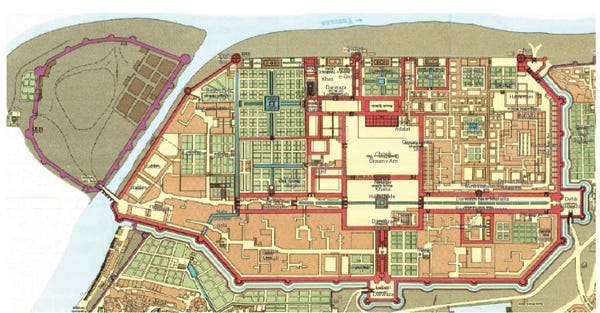

The Mughals conceived the city, in accordance with traditional Islamic theories of architecture, as the meeting point of heaven and earth. The city was situated between the two major poles of man and the cosmos, therefore becoming a sacred centre that encompassed the empire and the universe. By extension, the emperor also had an elevated significance, being the symbolic centre in the hierarchy of City, Empire, Universe. The capital city of Shahjahanabad, built in 1638, expressed this belief in its plan that was monumentally laid out alongside some Hindu influences, with the city symbolising the cosmos and its eight massive gates, the four cardinal directions and the four gates of heaven. The main boulevard of Chandni Chowk lead from the Emperor’s fortress-palace, which was in itself a city within the city, to the Fatehpuri mosque at the other end, flanked by other boulevards and avenues running across the plan. The boulevards, although active and redeveloped today to incorporate other uses, were marked by axial symmetry, from the fortress-palace, past symmetrical sculptures and buildings to the mosque which is also a composition along the processional axis. Partially destroyed and redone by the British, and subsequently by governments, today, when they are seen as part of one continuous movement, the individual bays of buildings may not have harmonic proportions and symmetry, but like music, they do hold a rhythmic relation within themselves. The strange thing about such architecture, or even edifice, is that despite changes and alternations, it retains the effect of solemn procession and its sanctity.

The aim of Islamic architecture was to create harmony and clarity, not tension and suspense. In accordance with these beliefs, the buildings were constructed in platonic shapes such as square, octagon or circle, often covered with a hemispherical vault or dome standing on arches, columns and pyramidal towers or slender spires, while entailing rich ornamentation styles, techniques, and motifs. Islamic architecture was based on the rules of mathematical proportioning, where the beholder can intuitively gauge the harmony consciously devised by the architect. In nearly all Muslim mausoleums, one can immediately feel the proportional relationship in the dimensions of the building, its openings, windows, rooms and gardens. Each element can be further divided perfectly into even parts, but the necessity to divide does not arise because from the largest building to the smallest motif, almost every size is perfectly and rhythmically encapsulated and expressed in the architecture, in scale and order.

In relation to the system of directions and proportions, even the famous innovation of the Charbagh, a garden setting inspired by the description of Paradise in the Holy Quran, was also assimilated. The gardens were conceived as quadrilaterals with a layout of four gardens traditionally separated by waterways, together representing the four gardens and four rivers of Paradise. It became a powerful method for the organization and domestication of the landscape, itself a symbol of political territory. Not just an escape from ceremony, here, nature was cultivated just as it was celebrated in poetry and art. Even though such architecture is symmetrical and strict, it does not overtly emanate an impression of having been created for ceremonies for its sheer completeness.

While Victorian and Islamic planning were pedestrian-oriented and stiff, cut to recent architectural and town planning, New York City represents a whole different kind of motor-oriented rhythm with its broad avenues and cross-streets. Simply a gridlock, it is experienced but differently by cars driven along the avenues. The two freeways on either sides, the Hudson Parkway and FDR Drive are unsurprisingly, unobstructed by any intersections and cuts, enclosing the city in between. This rhythm is not something new, but perhaps tailored to lifestyles and mindsets of current times in the United States that make it function differently. And it is interesting to note, that this rhythm does not necessarily work in every other part of the country or even world. Barcelona gradually depleted while following its own grid plan. Asian cities require an entirely different kind of proportioning system to accommodate their lifestyles and populace.

Because architectural design, while being stationary, must be expressed according to the nature and density of movement that will flow through them. Previous eras of history displayed designs that were based on then beliefs of adherence, uniformity and conformation. But with changing mindsets and attitudes, the need to be able to adapt and change is imperative. Maybe this is one of the reasons that led to the decline of Detroit, and the rise of New York City that still attracts and assimilates people from everywhere. When the rhythm of physical design cannot keep up with the rhythm of prevalent life, all other systems - economic, social, cultural, etc. are destined to decline.